Article published on August 30th 2017

After a three-year stint in the Army as an ammunition specialist during the late 1970s, Christopher Driggins, now 57, found himself still fighting, long after his military career ended. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) had taken hold of his life and he withdrew socially. His salvation came in a surprising form: a Goffin’s cockatoo named Cezar.

The Vancouver, Washington, veteran already kept a few birds of his own as a hobby when he learned of a family that no longer wanted their bird. Driggins drove out to the home to find the bird cooped up in a small cage in a garage that reeked of gasoline. He rescued Cezar that day, but Cezar also rescued him.

“I took him with me everywhere,” Driggins says. “He was riding on my shoulder, riding in the car with me on a perch. And I realized I was becoming more sociable.”

With Cezar in tow, people would strike up conversations and help Driggins make connections. Funny one-liners were one of the duo’s specialties. “A lot of people would ask ‘Oh, does your bird talk?’” So Driggins taught Cezar the tongue-in-cheek reply: “Can you fly?”

The more he worked with Cezar and his other birds, the better Driggins felt. “At the end of the day, all I could do was think about the birds,” he says. “What am I going to do for them in the morning? What’s our day going to be like? The next thing I knew, I wasn’t having anxiety when I went to bed. The nightmares started going away.”

Inspired by his bond with Cezar and his newfound zeal for life, Driggins made it his mission to spread that same joy to other veterans. In 2015, he founded Parrots for Patriots, an organization that places rescued birds with veterans seeking companionship. For many service members, a dog or cat that lives only 10 to 15 years can be another source of sadness, but birds can live to be 40 or even 80 years old.

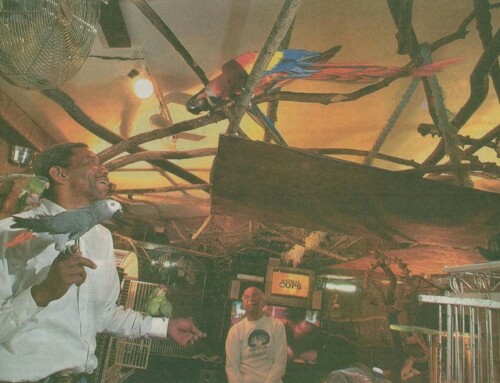

Parrots for Patriots founder Christopher Driggins and loyal volunteer Chelsey Marcusen spend time socializing Cezar and friends. (Helga Childers)

“I know there are hundreds of veterans out there who don’t know what birds can do for them,” he says. “It’s so touching to see other veterans come out of their shell.”

Since its founding, Parrots for Patriots has placed more than 140 birds, rescuing abandoned birds and training them. Driggins teaches many of the birds to salute, something that’s a special surprise for veteran adopters.

Between his own birds and temporarily housing birds before they are adopted, Driggins has a home full of tweeting friends. And he wouldn’t have it any other way.

“They saved my life,” he says. “I’m appreciated every day by them, and without their love and appreciation, I don’t think I would keep moving forward.”