Early every morning, a perfect falsetto disrupts Paul Thomas’ dreams as Magoo, one of his talking African gray parrots, alerts him that it’s time to face the day.

Within minutes, another parrot, Sabrina, and a cockatoo named Murphy are also chiming in, leading Thomas to sigh and reach for his slippers, then smile, knowing that his birds will greet him with friendly squawks and a wisecrack or two.

“I tend to them and they tend to me,” says the former Air Force firefighter… Read entire People Magazine article

“I tend to them and they tend to me,” says the former Air Force firefighter, 36, who suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder. “They give me a consistent, enjoyable daily routine filled with love and respect. It’s like having toddlers who just want to Velcro themselves to you. It’s pretty sweet.”

Thomas, who lives in Battleground, Washington, is among nearly 100 disabled veterans who have found happiness and new meaning in life by taking in abandoned birds that have been trained and donated by Parrots for Patriots, a program founded by Christopher Driggins of Vancouver, Washington.

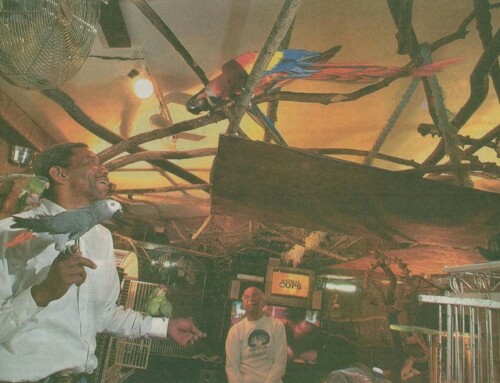

“It’s a new chance at happiness for both birds and the veterans,” Driggins, 57, who also runs Northwest Bird Rescue, tells PEOPLE. “Taking care of a bird helps give the veteran a sense of responsibility and duty and something to spoil with unconditional love. And for the birds, they’re happy to have a kind person in their lives — somebody who cares. The bonding that happens is incredible to witness.”

Driggins knows firsthand the therapeutic powers of matching unwanted parrots with veterans in need. A former Army veteran who was stationed with the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, he suffered from PTSD for years following his military service, until he started Northwest Bird Rescue in 1988.

Four years ago, while on a call to pick up a parrot whose owner had died, he noticed the man’s office was filled with medals and plaques that he’d received from years of military service.

“It got me thinking that perhaps there really was something to the calming effect of having birds around,” he tells PEOPLE, “so I decided to share the wealth of what my feathered friends had done for me.”

Driggins now matches unwanted or abandoned parrots with any veteran desiring companionship and something to care for.

“These birds make you laugh and smile and, as a bonus, they know how to mimic quite a few one-liners,” he says. “I’ve also taught several of them how to salute, which is always a nice thing for any veteran.”

For Troy Francis, 29, who has suffered from insomnia and anxiety since serving in the Navy, having two talkative parrots to tend to has brightened his life in ways he never imagined.

“My green cheek conure, Kiwi, helps calm me down every night before bed,” says Francis, who lives in Spanaway, Washington, and works as a surgical technologist.

“Sometimes, I have nightmares about an accident on my ship that killed a close friend,” he tells PEOPLE, “and just petting and being with Kiwi helps. We share breakfast every morning and she likes to take a shower while I clean the dishes. She’s made a big difference.”

To qualify for a bird through Parrots for Patriots, veterans pay a $25 application fee and agree to home visits and a training session before their adoptions are approved.

“Parrots live a long time — up to 80 or 90 years for some breeds,” says Driggins, “so they are companions for life. It’s a huge commitment on the part of the veteran, but it’s also a huge joy for them to have something to look after and bond with.”

And if they also know how to sing a few words of the Star-Spangled Banner, “it’s an added benefit,” he says. “I once had six gray parrots who all sang, ‘Row, Row, Row Your Boat’ at the same time. It drove me nuts, but there is good news: You can always teach a parrot a new song. And the bird will be more than happy to sing it for you every morning.”